The euphoria about the better-than-expected farm performance in the current agricultural year may be short-lived. The drought may not have had the impact that most of us feared, but has still been instrumental in putting agriculture back on the agenda. As if the erratic monsoon was not enough, the massive failure on the price front at the consumer and producer end will be difficult to ignore whether in relation to growth or food security and livelihood.

It is obvious that agriculture is in crisis but it would be pre- mature and naive to blame this on the monsoon failure.

The crisis is deep-rooted and is a result of years of neglect, especially in the last decade or so.

Given the declining share of agriculture in the gross domestic product (less than 17% last fiscal), this may not be worrying to those who judge its value in terms of this con- tribution. But things get more complicated from the point of employment, livelihood and food security.

Agriculture remains the big- gest employer, with more than half of the Indian population depending on it for livelihood.

However, its share of total investment is ridiculously low at around 7%, having dropped from an average 10%-plus during the National Demo- cratic Alliance regime and around 20% in the beginning of the 1980s. Although there has been a recovery in abso- lute terms since the United Progressive Alliance took over in 2004, in real terms, public investment in agriculture has remained less than what it was in 1980-81. It has in- creased by an average 2% per year in the last 27 years, less than the average rate of growth of agricultural output.

But the neglect in financial investment and allocation is only part of the story. In the last two decades, there has been a collapse of extension services, which are meant to educate farmers on the latest research and techniques to help them raise productivity.

In the Situation Assessment Survey of Farmers in 2002-03, only 8% said they had re- ceived information from ex- tension services or through government demonstrations.

The slump is linked to the de- cline in the agricultural re- search system, which has suf- fered as a result of under-in- vestment and technological stagnation.

The mismanagement on the price front comes on top of all this. The situation has been worsened by political inter- vention in agricultural pricing, particularly in foodgrains such as rice and wheat. As men- tioned earlier, the procure- ment and public distribution systems aren't helping pro- ducers or consumers. The dra- ma surrounding sugar cane pricing was only one aspect of this. While farmers struggled to get remunerative prices for sugar cane and consumers paid through their nose, the sugar mills saw profits surge.

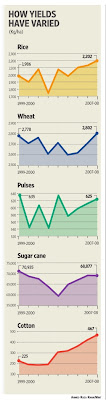

The net result has been the deceleration in yields and in- creased vulnerability to weather fluctuations. Between 1999-2000 and 2007-08, the average rate of growth in yields was 1.3% for rice and 0.1% for wheat. On the other hand, the yield in pulses de- clined at the rate of 0.2% per annum and that for sugar at 0.4% per annum. The only major crop which saw yields increase by more than three times in the past five years is cotton, thanks largely due to the adoption of Bt cotton.

Compared with this, rice yield grew at 2.7% in the 1980s, wheat at 3.4%, pulses at 2% and sugar cane at 1.2%.

Naturally enough, total annual foodgrain availability has de- clined from 186.2kg per head in 1991 to 160.4kg per head in 2007.

Fortunately, agriculture is back on the agenda. Not be- cause of the farmer's plight but because of food price in- flation, which is fuelling gen- eral inflation that has now gone beyond acceptable lim- its. This is despite the farmer putting up a much better per- formance than expected. Un- fortunately, the government has mismanaged the food economy so badly that even increased production is of no use. How else does one ex- plain the fact that vegetable production has increased 5% but vegetables remain the driver of food price inflation?

Of course, there are limits to what we can expect from the Budget. Partly because ag- riculture remains a state sub- ject and very little can be achieved unless states also contribute.

But at the Central level, some urgent measures are needed, among them a step- up in agricultural investment, particularly in irrigation in dry-land areas, research and extension. Secondly, there has to be an increased effort to re- duce regional inequality with particular attention to the eastern states and dry-land ar- eas. Third, there is an urgent need to reform agricultural marketing, including a revamp of the Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee Act.

Finally, there has to be a concerted effort in managing the food economy, including changes in the procurement and public distribution sys- tems. There is no better time than this to enact the National Food Security Act.

While these are some of the short-term measures that may be essential, there is an urgent need to have a long-term vi- sion for agriculture and farm- ers for inclusive growth. And that includes a strategy for im- proving the profitability of ag- riculture. This is not only es- sential for maintaining the growth rate of the economy but is necessary if there has to be any meaning to the agenda of inclusive growth. How can one think of inclusion if more than half the population is ex- cluded from the growth pro- cess?

Himanshu is assistant professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and visiting fellow at Centre de Sciences Humaines, New Delhi.